Woodbury Professor Uses Language—and Humor—to Take on Sexual Harassment in the Art World

In recent months, the #MeToo movement has pulled back the curtain on the enormously pervasiveness of sexual harassment across a variety of professions worldwide. Now, Woodbury faculty member Emily Bills has teamed up with Florida Atlantic University’s Karen Leader to create a framework to help those who have suffered harassment within the arts community.

Bills, who teaches Urban Studies in the College of Liberal Arts, and Leader gave a presentation as part of a special panel on sexual harassment at the College Art Association (CAA) Conference in Los Angeles in February. The goal of the panel was to identify larger issues shaping sexual misconduct in the arts and to form a set of recommendations to be developed into a framework for CAA best practices. Their presentation addressed intervention at the level of language.

“We discussed how victims of sexual harassment are frequently unheard,” Bills said. “When they’ve expressed discomfort in workplace situations, when they’ve reported their concerns, when they’ve said no, when they’ve told stories of assault. We are particularly interested in how language can be used during the moments of intervention and reaction, asking whether it’s possible to introduce into cultural consciousness simple phrases that are comfortable to use but effective in diffusing harmful situations.”

Bills and Leader asked whether such language could be harnessed to encourage bystanders to partner in prevention and would-be harassers to rethink their actions. They conducted various forms of research, including speaking with colleagues in the field, to identify the most frequent scenarios in which people—particularly those in the fine arts and history—experience gender discrimination and sexual harassment.

“One scenario is a studio visit—a situation where artists have frequently experienced harassment almost to the point of normalization,” Bills said. “Studio visits take place in private, the artist is in a vulnerable position, and the dealer, curator, or professor holds a position of power. We then developed what we call the ‘#actually campaign’ and presented it at the conference.”

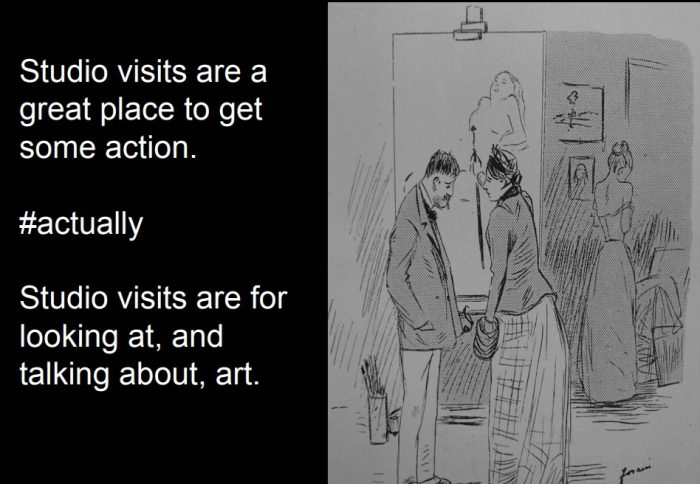

The “#actually campaign,” which included cleverly-paired images from art history to accompany their rejoinder, was designed to bring humor to what is often a fraught and intense conversation.

In the studio visit scenario, for example, their text reads: “Studio visits are a great place to get some action.” While the rejoinder states: “#Actually” “Studio visits are for looking at, and talking about, art.

“We paired this with a drawing by Jean-Louis Forain, called “Femmes D’Artistes” where a man is pictured watching a woman paint, while a model is half undressed in the background,” Bills explains. “The drawing’s context may not relate to the topic we discussed—although visually there is a connection—but this is the ‘shamelessly misappropriated image’ part!”

Another example:

She was just being flirtatious. You’re lucky she singled you out. I bet she’ll help you make connections. #Actually: That is completely unprofessional. Would you like me to bring the proper authorities into this?” This was accompanied with a painting by Gustave Moreau of “The Apparition.”

“We feel humor is a great leveler and can help us move beyond #metoo and #notallmen to developing useful phrases that ideally become part of our cultural consciousness,” Bills said. “Our ultimate goal is to partner with an artist to produce a pocket guide for your favorite ‘ally guy.’”

The presentation received an overwhelming positive response from those at CAA. But, in addition to getting laughs, it also elicited some serious conversation.

“We wanted to strike back against the normalization of certain tropes in the art world,” Bills explained. “From the gallery attendant as sexualized “fashionista” who is expected to flirt with clients, to the trivialization of bad behavior by ‘genius’ academics who have made important contributions to scholarship. These things are never okay.”