On Location with Dr. Jennifer Peterson: The Spectacle of Outdoor Shooting in the Silent Era

What goes around comes around. Dr. Jennifer Peterson, chair of the Department of Communication, associate dean of the School of Media, Culture & Design, and associate professor at Woodbury, can attest to that.

What goes around comes around. Dr. Jennifer Peterson, chair of the Department of Communication, associate dean of the School of Media, Culture & Design, and associate professor at Woodbury, can attest to that.

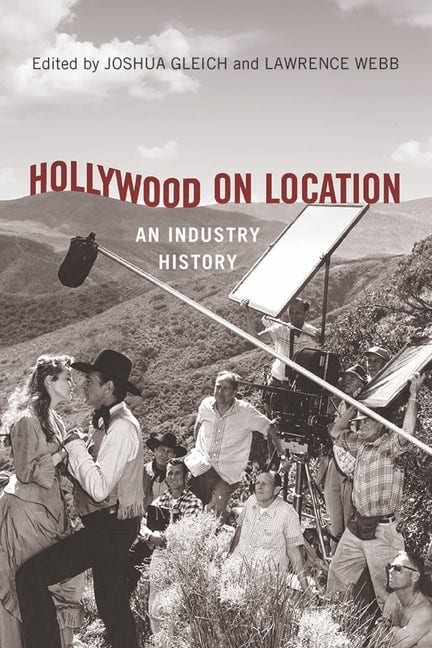

Dr. Peterson has published the first chapter in Hollywood on Location: An Industry History (Rutgers University Press). Her contribution, “Location Shooting in the Silent Era,” advances the idea that location shooting really didn’t emerge until the consolidation of the Hollywood studio system around 1917. “Before the mid-1910s, there were so many varieties of location shooting, and so many different places where the film industry was located, that it was a challenge to make sense of all the different practices,” she says.

A century later, there’s more than a little sense of déjà vu. “Film is not just fiction films with stories, characters and movie stars,” Dr. Peterson observes. “Film is also a technology, and a medium of capture. Nonfiction films – that is, films that did not tell stories, but instead observed something – were more common in early cinema than story films. We’ve seen a return to this in digital media today, with the rise of YouTube and the return to short, ephemeral moving images.”

Hollywood on Location is the first comprehensive history of location shooting in the American film industry, chronicling how that mode of filmmaking changed the industry’s business practices, production strategies and visual style. As editors Joshua Gleich and Lawrence Webb note, “whereas studio filmmaking sought to recreate nature, location shooting sought to master it, finding new production values and production economies that reshaped Hollywood’s M.O. Location shooting has always been a vital counterpart to soundstage production, and at times, the primary form of Hollywood filmmaking. But until now, the industrial and artistic development of this production practice has been scattered across the margins of larger American film histories.”

Organizing the emergence of location shooting in a new way, Dr. Peterson’s article sets forth a three-part taxonomy of location shooting during the first decade of film history:

- Scenic films (films about existing geographical places)

- Outdoor shooting (films shot outside but not set in any specific location – e.g., “How It Feels to Be Run Over”)

- Actuality footage framing a staged drama (“Execution of Colgosz,” Edison/Porter, 1902 or “The Country Doctor,” D.W. Griffith, 1909)

“From the start, what I call ‘outdoor shooting’ was actually more common than studio film shoots,” she says. “There are a couple reasons for that. First, movie shooting required bright lighting, and artificial lights were not yet available. Second, it was, at that time, just simpler and cheaper to shoot outdoors.”

According to Dr. Peterson, films made during the industry’s first dozen years embraced spectacle, showing rather than telling. “Around 1906, the ‘cinema of attractions’ gives way to the so-called ‘cinema of narrative integration,’ which means films that [do] tell stories,” she explains. “At this point, location shooting starts to take on its more familiar trappings: locations as fictional settings. But even then, the film industry didn’t look like it does today. It wasn’t until the industry moved west and the studio system emerged that what we now understand as ‘location shooting’ came to be.”

As it happened, the back lot was never all that far away. The original “Ben-Hur” tried location shooting in Italy in 1923, but after a series of production and personnel delays, Hollywood proved to be both the practical fall-back and the proper venue for spectacle. As Dr. Peterson recounts, “the most famous scene, the chariot race, was shot on a specially constructed set on the MGM back lot in the spring of 1925.”